This is a draft paper, based in part on some of my older blog posts and continuing and building on those ideas in conversation with the work of Ivan Illich and others. I’m presenting this today–momentarilly–at the 2021 4S conference.

Abstract

The last two decades have seen an increase in the number of online university classes operating under any of several commercial Learning Management Systems (LMS). Online classes expanded dramatically in the US during 2020 as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Students, faculty, and administrators frequently assume that LMSs are epistemologically and ontologically neutral. These LMSs are designed to do exactly what they say on the tin: they are systems for managing learning. At the same time, they function based on implicit understandings of “learning,” “management,” and “systems” that privilege some knowledges, interactions, and discourses while de-emphasizing others. Specifically, these systems tend toward a focus on knowledge-as-thing over knowledge-as-process. In this paper I argue that the LMS as a tool is not—in the terms of Ivan Illich—convivial. Rather, LMSs as designed enforce a technocratic perspective based on efficiency and replicability. At the same time, problems with LMS-hosted classes are defined in technological terms, with additional improved software being seen as the main solution. I argue that carefully considering the LMS as a medium for coursework can allow instructors (and students) to draw on the platform’s strengths without submitting to the logic of the LMS as a tool.

Introduction

In 1987, I was an undergraduate student in Biology at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville (UTK). My father was, at the time, working as a mechanical engineer for E.I. Dupont in Memphis. It was the Fall semester of that year when I sent my first email across the state. As I recall, it was sent over BITNET, the routing information was embedded in the email address, and it took him by surprise when the message showed up on his company computer. My chemistry class that semester, taught by Dr. Donald Kleinfelter, was one of a few classes that was broadcast across the campus’ closed-circuit television system—so students could attend from their own dormitories. At the same time—in the Fall of 1987, the NKI Distance Education Network in Norway rolled out their first course using the EKKO Computer Conferencing system (Paulson and Torstein, 2001). These first steps were tentative, experimental, and isolated.

It wasn’t until the late 1990s and early 2000s that Learning Management Systems (LMSs) became common. These are more than single course broadcasts or bulletin boards. Their work includes attendance tracking, communications, information hosting and sharing, scheduling, assessments, grouping students, managing users and user roles, and tracking click-throughs and time spent on individual web pages. A working LMS provides consistency across classes for students and instructors. It facilitates standardization and replicability. And, I argue, it is too often assumed to be politically and ethically neutral. These LMSs are designed to do exactly what they say on the tin: they are systems for managing learning. Or, at least, they are systems designed to manage the institutionalized educational process. At the end of the day, though, they end up also managing learning—in ways that may be unintended or perverse.

Online classes—synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid—were already becoming more popular through the first part of the 21st century. The U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics tracked a continuous increase in the number of online classes from 2012 through 2019. In the Fall of 2018, 35% of undergraduate students in the US enrolled in some type of distance education course enrolled in some type of distance education course (NCES 2021). This doesn’t count those students taking face-to-face or hybrid classes where a portion of the class is hosted and administered through a LMS.

Then, of course, the pandemic hit. Faculty and students who had avoided talking classes online or using LMS technology were now all in. I don’t pretend to know what this shift will mean in the medium or long term, but others are less hesitant about making predictions. As Sean Palmer and Jason Gallagher wrote in the Harvard Business Review in September 2020:

“This moment is likely to be remembered as a critical turning point between the “time before,” when analog on-campus degree-focused learning was the default, to the “time after,” when digital, online, career-focused learning became the fulcrum of competition between institutions.” (Palmer and Gallagher 2020)

Time will tell, but what strikes me here is not the assertion of a turning point but the expected shift from “degree-focused” to “career-focused” learning. This is certainly in line with a perceived increase in neoliberal managerialism within universities and a shift in how the educational project is valued.

Online Classes as Solutions and Solutionism

Online classes in general and LMSs in specific seem to be riding a wave of inevitability. At my own University—prior to the pandemic—the available LMS was gradually and unevenly adopted by faculty for their courses through the last decade. We were encouraged to make use of the LMS even for face-to-face classes to host syllabi, articles, and the class gradebook. This was often described in terms of accessibility (so that differently-abled students could access and read materials) and security (since maintaining a gradebook on paper or a laptop risks leaking personal information.) In these cases, the LMS does provide solutions. LMSs, particularly in the case of online classes, also taut the potential to increase enrollment, retention, and course success. Whether they actually do these things is beyond my scope here—though during the last decade in the US, as online participation has increased, total enrollments have dropped (NCES 2021).

What does interest me here is the way that the LMS technology bootstraps itself forward. LMSs follow a familiar technological trajectory: from existing as a curiosity, to useful tool, to ubiquitous and even mandatory technology (Illich 1973). Particularly in light of the rapid adoption of LMSs since the pandemic, this also raises concerns about the technology’s influence on pedagogy and the data security of students (Teräs et al. 2020). Universities are placing increased priority on technological integration—so that the LMS works with other digital systems to allow a seamless flow of data across platforms. This has the additional effect of locking the LMS into the campus technological ecosystem. While I have several friends who have given up smart phones, or cars, or even tried moving partially off of the electrical grid, I don’t know anyone who has ditched the LMS—except by leaving academia.

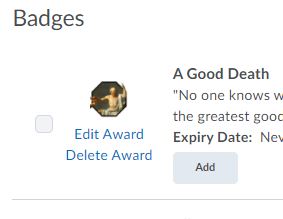

Where students and faculty see issues with the LMS, the LMS itself provides the solution. Low online engagement? Intelligent agents within the LMS can monitor student logins, activities, and clicks and send out automated emails to students. Students not excited about the course? The LMS provides fun digital badges to gamify the class experience. Lots of papers to grade? The LMS both integrates with plagiarism-checking technology and provides easy-to-use rubric tools for quantifying student work. As an anthropologist who works largely in the qualitative world, that one hits particularly hard. Before we had the word “solutionism” Ivan Illich described this process: “It has become fashionable to say that where science and technology have created problems, it is only more scientific understanding and better technology that can carry us past them” (Illich 1973, 16).

There are, of course, problems that the LMS does not address. In both face-to-face and online classes, many instructors have worked to subvert the institutionalized tendences of the education system, whether through ungrading, embodied pedagogies, democratizing the classroom, or decolonizing practices. And here is the first point of technological non-neutrality that I want to raise. Face-to-face instruction is also a technology of learning management, but it is one with greater plasticity and less potential for casual surveillance. Which brings me to conviviality.

Can a LMS be Convival?

Ivan Illich developed the concept of conviviality to describe tools that we can live with. Illich is by no means against new technologies. He envisions convivial tools as affording opportunities without compulsion:

“Convivial tools are those which give each person who uses them the greatest opportunity to enrich the environment with the fruits of his or her vision” (Illich 1973, 29).

“Convivial tools rule out certain levels of power, compulsion, and programming, which are precisely those features that now tend to make all governments look more or less alike” (Illich 1973, 24).

He contrasts these to managerial or industrial tools:

“Industrial tools deny this possibility [conviviality] to those who use them and they allow their designers to determine the meaning and expectations of others. Most tools today cannot be used in a convivial fashion” (Illich 1973, 29).

His concern is that once a particular technology crosses a threshold of institutionalization, we begin to conform ourselves to the logic of the tool.

“The use of industrial tools stamps in an identical way the landscape of cities each having its own history and culture. Highways, hospital wards, classrooms, office buildings, apartments, and stores look everywhere the same. Identical tools also promote the development of the same character types. Policemen in patrol cars or accountants at computers look and act alike all over the world, while their poor cousins using nightstick or pen are different from region to region. The progressive homogenization of personalities and personal relationships cannot be stemmed without a retooling of society” (Illich 1973, 22).

Illich himself was very interested in education and education technologies—though the technologies he was considering consisted of standardized textbooks and classrooms. And it is fairly clear to me that he would describe the ubiquity of the LMS as a case of non-convivial or industrial technology. This brings me to me central question: can a LMS be convivial—if we can just figure out the right way to use the tool? TL;DR: My answer is provisionally no.

As I see it, the use of the LMS—particularly in online classes—distorts the user-tool relationship. In 1950, Alan Turing developed the idea of the Turing Test–the core idea being if a computer can respond in a way that is functionally equivalent and indistinguishable from a thinking (human) user, then that machine is also thinking (Turing 1950, Harnad 2003). I want to propose the inverse: if a human responds in a way that is indistinguishable from a machine, then that human is an artificial intelligence. What if, in working with computers, we are adapting our own social-cognitive processes to the system to such a degree that we ourselves are essentially apps, to be judged as either functional or buggy? Rather than humans using machines as mere tools, the computer system interfaces with us as an aggressive act–demanding specific data in specific formats. How many of the students in our online classes would pass a Turing Test? Put another way, if an AI signed up for an online class would we know the difference? Rather than AI being the product of human invention, AI enters into us through an unbirth as an emergent property of the machine system.

In my online classes, I see students responding by hitting all the appropriate check-boxes. They submit papers, take quizzes, do the readings, watch the videos, and participate in the discussion forum. They meet the objective standards that I set in the course development process. They write papers, post in the discussion forum, upload videos, and so on. When I assign group work, it is always mediated by technology (email, Groupme, discussion board, Skype)–except when online students happen to share offline social connections. And I see students learning–they leave the class with new information, and often with new perspectives on theory, or communities, or whatever the topic of the class was. At the same time, I am left with a nameless dread.

Are these students engaged participating in a learning community that serves as legitimate peripheral participation (Lave and Wenger 1991) for membership in the larger community of anthropologists? Yes and no. I do think that the students in this class are engaged in the work of culture-building. The question is, what kind of culture are we (I include myself) assembling, what are the scraps that we are drawing together, and what tools and processes are we using along the way?

I think two components of this issue are synchronicity and embodiment. The LMS is apparently an asynchronous environment, meaning that students and instructors are not interacting with one another in real time. Zoom and live text chat are available, but they both flatten and delay communication. The asynchronous nature of classes could be seen as a benefit by students who dislike groups, crowds, and potentially uncomfortable social situations. Having an asynchronous discussion via a forum allows students time to compose their thoughts and draft an “appropriate” response. All of this, I think, works against the development of either an online culture that is conducive to critical discourse or a learning community that transitions students into the discipline of Anthropology. Asynchronous classes limit shared experience, emotional communication, and the tension of existing in an uncertain liminal state.

I say that these classes are apparently asynchronous, and–but not from the perspective of the machine. From the computer’s view, communications between itself and others are always synchronous. The computer-user relationship is the only synchronous sharing of experience that the technology allows, and in this case synchronous sharing is both implicit and mandatory. If, as I suspect, synchronous sharing of experience is one necessary component for cultural change, then the culture that is emerging will likely focus on narrowly-defined technological integration and information sharing, governed by invisible technocrats. Ruth Benedict famously said that the purpose of anthropology is to make the world safe for human differences–which is contrary to the kind of standardization that online classes so often demand.

Similarly, the experience of both faculty and students is differently embodied in face-to-face versus face-to-LMS interactions. In both situations, I would say, human participants are fully embodied; and in both systems, embodiment is affected by the structural arrangements of technology, whether that be desk in rows, whiteboards, screens, or phone keyboards with haptic feedback. The human-LMS interaction may seem to offer additional freedom, since you can be most anywhere (at a table, in the tub, driving) for the process. But, I think that this has to be weighed against both the narrow field of view that the screen requires and the work of educators to recognize and address embodiment in pedagogy—which is made more difficult by the LMS. Paul Drijvers in Utrecht has written on ideas about embodiment and physicality in math education (Drijvers 2019). I think these issues of synchronicity and embodiment are also too often taken as neutral.

I also argue that LMSs are not epistemologically neutral. In my own anthropology classes, on human prehistory, urban communities, the Internet, and so on, a frequent topic is the importance of material culture and the idea that tools—from stone scrapers to computers—are full participants in our bio-cultural systems, and that they affect our consciousness and communities in significant ways. In fully online classes, though, I meet a disproportionate amount of skepticism on this concept. In my experience, the LMS interaction also privileges an objective/transactional discourse of knowledge, which makes it more challenging to discuss other metaphorical approaches to knowledge (Kakihara and Sorensen 2002). My data and conclusion is preliminary, but I suggest that this skepticism is at least in part an artifact of the medium of discussion. If true, that has implications well beyond a few anthropology classes.

Lingering Questions

I am not entirely opposed to the LMS in principle, but—following Illich—I think that communities should limit the use and spread of tools to prevent them from becoming dominating institutions. In my own classes I am increasingly directing students away from readings, videos, and the like and toward their own families and neighborhoods. After thinking about this for a while, I’m left with some questions. Should an LMS be convivial? I’ve taken this as an assumption based on my own leanings and Illich’s work. Convivial for whom? It is possible to imagine a system in which LMSs are more convivial for faculty than students, or vice versa. What might be appropriate limits on LMS technology, who sets those limits, and how? Perhaps most critical—how can we overcome the assumptions of ethical and epistemological neutrality that so often accompany technologies like the LMS.

References

Drijvers, P. (2019) Embodied instrumentation: combining different views on using digital technology in mathematics education. Eleventh Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands. hal-02436279

Gallagher, S., & Palmer, J. (2020). The Pandemic Pushed Universities Online. The Change Was Long Overdue. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/09/the-pandemic-pushed-universities-online-the-change-was-long-overdue

Harnad, S. (2003). Minds, machines and Turing. In The Turing Test (pp. 253-273). Springer, Dordrecht.

Illich, I. (1973). Tools for Conviviality. Harper & Row.

Kakihara, M., & Sørensen, C. (2002). Exploring Knowledge Emergence: From Chaos to Organizational Knowledge. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 5(3), 48–66. https://doi.org/10/ghm59v

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press.

NCES. (2021). NCES Blog | Distance Education in College: What Do We Know From IPEDS? https://nces.ed.gov/blogs/nces/post/distance-education-in-college-what-do-we-know-from-ipeds

Paulsen, M., & Rekkedal, T. (2001). The NKI Internet College: A review of 15 years delivery of 10,000 online courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 1(2). https://doi.org/10/gm26c8

Teräs, M., Suoranta, J., Teräs, H., & Curcher, M. (2020). Post-Covid-19 Education and Education Technology ‘Solutionism’: A Seller’s Market. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(3), 863–878. https://doi.org/10/gg49t7

Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind, LIX(236), 433–460. https://doi.org/10/b262dj